Ellery Schempp was just 16 when he staged a silent protest of his school’s morning devotionals. Every morning, during homeroom, a student read 10 Bible verses over the public address system, and in homeroom, the teacher would lead everyone in the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer.

On June 17, 1963, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Ellery’s protest in the landmark school prayer case, Abington v. Schempp. To mark the ruling’s 50th anniversary, I wrote a profile for The Atlantic of Ellery. Ellery’s is the kind of story every teenager should study.

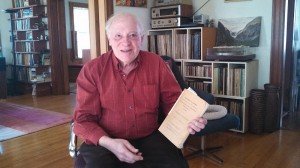

Ellery Schempp holds copy of Supreme Court ruling in his suburban Boston living room. Photo by Linda K. Wertheimer

Ellery, as a high school junior, brought a Koran to school and read that instead of listening to the Bible verses. He stayed seated and silent when the Lord’s Prayer was read. The Supreme Court, in 1963, ruled 8-1 in the Schempp family’s favor, deciding that state-mandated Bible readings and prayers were illegal. Fifty years ago, it wasn’t just Ellery’s school that required the prayers; the state of Pennsylvania and nearly three dozen other states did, too. Ellery’s school, like many, relied on the King James version of the Bible, used predominantly by Protestants. What his school did would not work for many students – Jews, Catholics, Unitarians like the Schempps, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, atheists, and many more.

As I wrote, a sense of unfairness motivated Ellery. He had Jewish friends, and they were uncomfortable when the prayer was read. He also had been learning about the First Amendment and understood that it was wrong to promote one religion over another in public school. And yet, I never learned about his case or others that came before or after it when I was in high school – in the 1980s. Neither did Jessica Ahlquist, an atheist who just last year opposed the presence of a prayer banner in her Cranston, R.I., high school. Coincidentally, the banner was a gift from Cranston High School West’s class of 1963, the same year as the Schempp ruling.

Jessica, who I met when she spoke during a panel discussion with Ellery in April, said she never knew about Ellery’s protest before he reached out to her during her own protest. He offered to speak on her behalf at a hearing. She wished, Jessica told me, that she had learned about Ellery in her high school. Perhaps if she and her classmates had, the decision to remove the banner would have been a no-brainer. Jessica credits her fairly easy court win to the groundwork set by Ellery and others.

Ellery’s protest is perhaps above all else a story about a young man who found the courage to speak up when no else would.

“It was his chutzpah that was fabulous,” Diane Moore, a Harvard Divinity School professor told me. She had Schempp speak to her religion and democracy class last December. “It was remarkable to me that a high school student took this on his own.”

Ellery’s protest started in the 1950s as the McCarthy era was ending and Americans were worried the Cold War. Conformity was in. Rebellion certainly was not. Ellery and his classmates told me that they took a risk in high school if they simply wore their hair too long or refused to conform to strict dress codes.

Ellery worried not just about himself. The only option for those who did not want to sit in was to be excused, and that often meant being sent to stand in the hallway. Children were made to feel like they were doing something wrong when in fact, it was the state – or rather the school – that had erred.

He recounts the dark side of what he experienced day in and day out from elementary through high school when students recited the Lord’s Prayer at their school’s bidding. Students had to listen. They could not debate.

My article on the Atlantic’s web site was among several that marked the 50th anniversary of the Schempp ruling. As I wrote, Justice Tom Clark made it clear that schools could teach ‘about’ religion and should do that. They just should not preach. As time went on, educators reached consensus on what was okay, under the Supreme Court’s guidelines, including religious clubs before and after school. For more on that aspect, check out The Christian Science Monitor’s in-depth piece by Lee Lawrence or read author Stephen D. Solomon’s op-ed in The Wall Street Journal. And if you have teenagers, share the articles with them.