My religion seemed immaterial through most of my nearly 25 years as a newspaper journalist. I wrote about education. I helped with coverage of the World Trade Center attacks on 9/11 and of the shuttle explosion over Texas in 2003. My faith was kept so discreet that one newspaper reader once chatted with me thinking I too was Christian. What did I think of those Jews who oppose prayer at public meetings, the caller asked me? I somehow managed to end the call without screaming at the bigot.

Now, as a writer of a yet-to-be-published memoir, I am open about my Jewish identity. I write this blog that I call Jewish Muse. My memoir is about my journey closer to my Jewish faith, a religion I felt little connection to throughout my childhood and early adulthood. I am starting to write for Jewish publications. And, on Oct. 3, I attended a Jewish authors’ conference run by the Jewish Book Council. I have become something I never used to call myself – a Jewish writer. Before, it was more like I was a writer who happened to be Jewish.

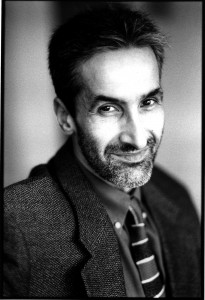

The one-day conference, titled “Jewish Authors Conference: Writing for the Adult Reader,” did not seem that different from other writing conferences. Author and journalist Samuel G. Freedman, a professor at Columbia’s school of journalism, gave a pep talk that applies to writers of any faith. He told us – roughly 25 writers of varying ages — that we can persuade ourselves just how tough publishing is and develop inertia. Or, we can truly believe in ourselves and eventually find our way to publication. “You’ll not lack for rationale to not write your book,” Freedman said.

Editors from major publishing companies and from Lilith, a Jewish magazine for feminists, spoke about how they work with authors and how they select manuscripts. Authors spoke about the challenges they face. The authors’ panel had the most Jewish content. The panelists – Gal Beckerman, Jennifer Gilmore, and Joanna Smith Rakoff – are all Jewish. Gilmore and Rakoff are novelists whose books have Jewish themes and/or many Jewish characters. Beckerman’s debut nonfiction book, When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone, is about the refuseniks who tried to save Soviet Jewry. A conference participant asked the authors whether they view themselves as Jewish writers and what it means to be a Jewish author. The question was dealt with briefly. The subject is a huge, complicated one. It could, moderator and author Erika Dreifus noted, produce enough fodder for a conference of its own.

Even as I am willing to be called a Jewish author, I am not sure exactly what that means. Yes, I am writing a book that shows how I grew closer to my Jewish faith. And yet, I hope that my story will appeal to readers diverse in faith and race. Dealing with tragedy is a universal experience. So is reaching out for something – whether it is faith, yoga, or a hobby – in the aftermath of loss. There is something universal, too, about a personal struggle to learn how to pray.

I sat in that recent conference and in part felt like I did at any other writing conference. I was a writer eager to learn more about her craft. I was a writer hoping to learn how to reach a wider audience. And yet, I felt something different, undoubtedly the goal when the Jewish Book Council organized the conference. I felt as if I were becoming part of another community – a community of Jewish writers. We may consider ourselves Jewish writers or writers who just happen to be Jewish. It does not matter what we call ourselves. We cannot prevent our life experiences from coloring the way we look at the world.

Note: Photo of Samuel Freedman is copyrighted by Samuel Freedman. Photo by Sara Barrett.